Back in September I wrote about the different understandings of what makes “authentic science learning” authentic and therefore engaging for students. Since writing that post, my Schoodic Institute colleagues and I have started a project that involves students in forest ecology and intertidal ecology research. And, yes, we have already seen how “authentic” work can quickly make a difference for some kids. In this post I want to sketch out some ideas for a research design that might give us insight into what “authentic” means to students and how it interacts with other features of the students’ personal and educational context to create outcomes.

My reasons for doing this sketching go deeper than just wanting to share thinking with others: I am looking for suggestions, critique, and feedback here. I say more about that at the end of this post.

Social Cognitive Theory

I really want to jump right into writing about the research design that I have been developing. But social science research necessarily starts from some particular stance about how and why people do what they do, and so it is useful to spend a moment saying something about the stance that informs this research design.

Social Cognitive Theory is a view of human decision making set forth by Albert Bandura (1986, 1997) in the last quarter of the twentieth century. As the name implies, it assumes that the choices that people make are influenced by other people (social), but it also assumes that people really do think about things and make choices. It does not take the view that choices are wholly determined by environment, social networks, genetics, economics, or something else. It is a “cognitive” theory in that it asserts that people really do think about things and exert free will to make choices based on their judgments not only about how things stand at the moment, but also about what they think is likely to happen in the future. This idea that people’s expectations have a lot to do with the choices they make is important in social cognitive theory. One particular aspect of “expectations” that Bandura thought about particularly carefully was “self-efficacy.” The idea here is that if someone does not think that they are likely to succeed in a particular course of action, they probably will not choose it. What is important is that the person’s perceived self-efficacy is not necessarily a good estimate of the person’s actual likelihood of success. So, self-efficacy emerges as a factor in decision-making that can operate independently of actual ability.

That’s probably enough theory. The point is that I am approaching students as people who make decisions, not as people who merely responding, without choice, to internal drives or external stimuli. (The fancy term for this is that I seem them as “agentic” — self-organizing, proactive, self-reflective and self-regulating as times change — in short, “agents.”) I see them as making choices on the basis of their perceptions of past experience and of their perceptions of what is likely to happen, which includes their perceptions of their ability to do different kinds of things.

Path Analysis

OK. Here is another term that I need to explain. “Path analysis” is important because I am proposing a research design that uses “path models” to provide a concise, testable description of how I think different kinds of “authenticity” end up making a difference. “Path analysis” is a way provide an empirical evaluation of a path model.

The easiest way to explain this is with an example. Dale Schunk (1984) studied the effect of different approaches to teaching division to children who had experienced difficulty in learning about arithmetic operations. He expected children to improve their division skill as a result of the instruction, but he also hypothesized that the instruction would increase the children’s sense of self-efficacy regarding division problems and their persistence in working on problems, and that both of these factors (they are called endogenous factors since they are affected by other factors in the model) would also have some impact on division skill. Finally, he hypothesized that greater self-efficacy would lead to greater persistence in problem solving. A path model is a way of expressing these conjectures graphically, like this …

The really useful thing about path analysis is that if you can measure the different variables in the model, including the output variable, it is possible use the correlations between the different measures to create estimates of the importance or “weight” of each arrow in the path model. (For those readers with a background in statistics, the weights are the amount of variance in the target variable that can be accounted for by variation of in the source variable.) When Schunk did that with the data that he collected, here was the result …

Notice that one of the arrows, between Instruction and Persistence, disappeared. The analysis showed that the Instruction did not have much impact on Persistence. Persistence definitely had an impact on the ability to demonstrate Division Skill, but increased Persistence turned out to depend on Self-Efficacy rather than on Instruction.

The analysis did indicate that although Instruction did impact Skill directly, there were even larger impacts that were “mediated” (an important word) by Self-Efficacy and, in turn, by Persistence.

Interestingly, although Self-Efficacy was improved by Instruction, most of the variation in Self-Efficacy was due to other things not included in the model.

The point here is that the path analysis provides a way to trim and evaluate the model. It is important that the path analysis does not “prove” that the model is correct. The reason is related to the observation that “correlation is not causation.” There needs to be some other reason or reasons to think that the model makes sense. The path analysis just helps in seeing whether and how the model works.

Modeling Authentic Science Learning

What kind of path model might make sense for authentic science learning? Answering that question leads to others:

- What are the output variables that we expect to see come out of authentic science learning?

- What are the “endogenous” variables that we think will matter in the operation of the model?

- What contextual conditions–things that are not affected by the model but that might have some impact on the model (these are called exogenous variables)–should we take into account?

Output Variables

One of the reasons I am writing this as a blog post is that there are a number of partner organizations–schools and non-profit organizations–that are collaborating with Schoodic Institute on this work. I really want to know what THEY think matters in the way of output variables.

I should also add that although I might think about measuring many things, each output variable requires a new model and extra calculations, not to mention a bunch of questions in a survey to collect information about the amount of change in the output variable. So, we have to really think that each output variable is worth investigating.

Having said all that, I came up with four. (I could quickly be persuaded to abandon one of more of these. Each additional output measure really does add a lot of work.)

- Change in students’ perceptions about the importance of science and/or technology to their expected career paths.

- Change in students’ perceptions of science as a useful, reliable source of knowledge.

- Change in orientation toward lifelong science or technology learning.

- Change in the student’s perception of social responsibility that reflects awareness of the way that living systems are made up of connected, interdependent elements.

These outcomes are a way of answering the question, “Why do we think it is important for students who are not much engaged in science–who may think that science learning is for other students but not for them–why do we think it is important for them to take another look at science learning?

The first outcome is because deciding that they can do science and that it is interesting might be a good thing for them in terms of career options. It is not to suggest that they should be involved in research–but just that some interesting career options might require them to think, “Yeah, I could succeed in learning about this.”

The second outcome is a form of “science literacy.” I would like for them to not think that science is some strange way of knowing that they cannot use or that is only for other people to think about — that is alien to them. It is a way of knowing that they can use.

The third one is another manifestation of science literacy and interest. My sense is that some citizen science programs value this as an outcome, so I include it here. This is the one that I would discard if I had to go with only 3 outcomes.

The fourth outcome is more connected to stewardship and place, coupled with a sense of the interdependence of systems.

The Models

I feel like I should really list all of the variables in the models before presenting the models. But I also suspect that reading through lists of variables without any sense of how they would be used would be boring and perhaps not meaningful. SO … I will begin by presenting the models for each of these outcomes. LATER — right after presenting the models — I say more about the variables. So, jump down to that if you need to know what the terms inside the models mean.

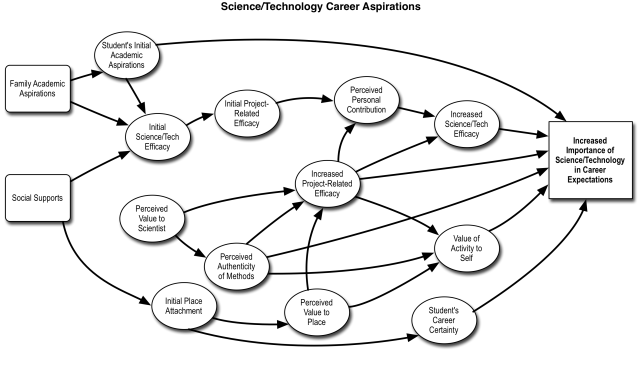

In each of these models I represent:

- Outcomes in a rectangle at the right, using boldface text

- Exogenous variables (outside factors not affected by the model) on the left in rectangles with rounded corners

- Endogenous variables (the things that we are measure to understand the internal workings of the model) in ellipses.

Also, each of these diagrams is kind of small within this blog post. If you click on the diagram it will open up, full-size, in a new tab.

Model: Science/Technology and Expected Career Paths

Two notes on this one:

- I figure that initial academic aspirations will matter directly to career expectations, apart from the authentic science learning activity. I also think it will matter in the operation of the authentic science learning.

- Perceived Value to Scientist, Perceived Authenticity of Methods, Perceived Value to Place, and Perceived Personal Contribution are related to the different perspectives on authenticity described in my earlier post.

Model: Science as a Useful, Reliable Knowledge Source

The roles of Place Attachment and Perceived Value to Place seem important here. I will be interested to see what the analysis shows.

Model: Lifelong Science/Technology Learning

Model: Social Responsibility / Awareness of Systemic Effects

Once again, I think that Place Attachment and Perceived Value to Place are probably important here. I also propose that Social Supports will have a direct effect on the outcome–but … we’ll see if that happens.

More on the Variables

Endogenous Variables

These are the variables that are inside the models. Here is the list that I am considering.

- Student academic aspirations

- Place Attachment

- Science/Technology self-efficacy

- Self-efficacy related to the work of the project

- Student certainty about career direction

- Perceived value of the activity to the student

- Perceived personal contribution to meaningful project outcomes

- Perceived value of the project to the scientist

- Perceived value of the project to place / community

- Perceived authenticity of the methods used in the project

The first four are self explanatory. Academic aspirations matter for a number of the outcome variables. I have a hunch that place attachment matters for some of them–this is one of the things I want to explore. Numbers 3 and 4 are obviously related to what we are doing in programs that involves students in science-related work.

The fifth variable is one that I stuck in as I was building the models. I am aware that career direction is very clear for some students and not at all clear for others. It seemed that this would matter with regard to some of the outcomes.

Variable 6 interrogates the student with regard to his or her perception of the project’s personal value to himself or herself.

Variables 7-10 are related to the different perspectives on authenticity described in my earlier post.

I have figured out a way to construct the survey so that we can look at the amount of change in a variable for each student as well as at values at particular points in time, such as fall, winter, and spring, while still maintaining anonymity for the students. I am thinking of variable #1 in terms of initial value, variables 2-4 in terms of the amount of change (and, in some cases, initial value), and variables 5-10 in terms of final values.

Exogenous Variables

These are the outside factors that might influence the model, but that are not influenced by the model. There are potentially many of these, of course. But parsimony is important, so I only include two that I think might account for a lot of variation in outcomes. Their inclusion is based on other research.

- Family academic aspirations for the student

- Social supports (family, friends, who the student can turn to).

What I Hope You Will Do

I have already spoken with some of you about participating with Schoodic Institute in this research, looking at the students in programs that you are running. This is a collaborative effort. For this research to work, I need data from lots of students. For it to offer benefit to you, you need to know what the research is about, and you need a chance to shape it. That’s what this blog post is about.

As you look at these models you will discover that they are complicated things. Putting this together took a full weekend. So, if you can find the time, think about them a bit, comparing them to your own experiences in working with kids and in seeing how authentic science learning appears to make a difference. Test the models against your own experience. Do they seem to represent plausible conjectures?

Again … the path analysis will not tell us whether the model is “true” or not. It will only take the model as given and tell us something about the relationships. So … the “truth” of the model needs to come from other research and from our own collective experience.

Also, if you think that there is something REALLY IMPORTANT to measure that I am forgetting, let me know. Conversely, if you think I am proposing to measure something that you feel does not matter, let me know that too.

Post a comment here on the blog if you want others to think about and perhaps respond to your thinking. Or … send me an email.

Thanks — I value your collaboration.

References

Bandura, A. (1986). Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. W.H. Freeman & Company.

Schunk, D. H. (1984). Self-efficacy perspective on achievement behavior. Educational Psychologist, 19, 48–58.